The History of Duboule

By the late 16th century master

watchmakers were

distinguished by their diversity and pure imagination; the sky was the limit for style and function alike. Timepieces were often made inside of pendants and charms shaped

into everything from human skulls to various animals like dogs, rabbits, and even fish. The more obscure the piece, the better. As the complexity of timepieces matured,

the distinction between watches and other types of jewelry became more defined. Actually, many early watchmakers were also goldsmiths and

engravers and yet many of these craftsmen did not sign their work. It wasn't until the early 17th century when watches first became true collectors items

that they required engravings of the creator's name.

By the late 16th century master

watchmakers were

distinguished by their diversity and pure imagination; the sky was the limit for style and function alike. Timepieces were often made inside of pendants and charms shaped

into everything from human skulls to various animals like dogs, rabbits, and even fish. The more obscure the piece, the better. As the complexity of timepieces matured,

the distinction between watches and other types of jewelry became more defined. Actually, many early watchmakers were also goldsmiths and

engravers and yet many of these craftsmen did not sign their work. It wasn't until the early 17th century when watches first became true collectors items

that they required engravings of the creator's name.

Then a jeweler and watchmaker by the name of Martin Duboule took signing to the next level when he added the phrase, "à Genève" underneath his name. This

revolutionary decision was first presented on a skull watch made circa 1620. Martin was  also known in his trade as a lapidary (precious stone engraver). This ability was well recognized when he created the earliest known Geneva watch decorated with champlevé enamel

that now resides in Paris' Cluny museum.

also known in his trade as a lapidary (precious stone engraver). This ability was well recognized when he created the earliest known Geneva watch decorated with champlevé enamel

that now resides in Paris' Cluny museum.

Throughout the early 1600's Martin Duboule took on apprentices such as Abraham Patru, Jean Brendon, and Charles Arbalestrier not only to teach them about making watches but also about engraving. In the end, one of his most prolific students turned out to be his own son, Jean-Baptiste.

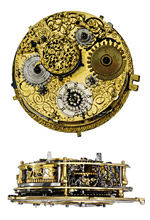

Jean-Baptiste Duboule soon became a master watchmaker and engraver in his own right. The astronomical fusee watch he made ca. 1680 now resides in the British museum and is claimed to be the finest piece ever made for its time. This masterpiece goes so far as to include separate dials for the day of the week (represented by the moon, sun, and the 5 known planets at the time: Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn), moon phase, day & night, the four seasons, and the month with corresponding sign of the zodiac. All of these functions are placed within a finely engraved perforated case so that the tiny bells inside could be heard when they chimed at the top of the hour. Its creator even went so far as to engrave every gear and winding mechanism inside that furthermore accentuates its exquisite beauty.

Jean-Baptiste would also gain recognition for watches created with

hand painted interior and exterior designs. His father made sure that he received a secondary apprenticeship in 1629 with Marc Grangier, a watchmaker and painter from

Châtellerault. Many timepieces of the day were created with metallic oxide paints upon a white enamel background. The subject matter of these miniature

paintings was just about as diverse as the cases and some were even portraits of the watch's owner. Jean-Baptiste, in particular, would often go so far as to explore

multiple enamel techniques on the same piece.

Jean-Baptiste would also gain recognition for watches created with

hand painted interior and exterior designs. His father made sure that he received a secondary apprenticeship in 1629 with Marc Grangier, a watchmaker and painter from

Châtellerault. Many timepieces of the day were created with metallic oxide paints upon a white enamel background. The subject matter of these miniature

paintings was just about as diverse as the cases and some were even portraits of the watch's owner. Jean-Baptiste, in particular, would often go so far as to explore

multiple enamel techniques on the same piece.

Jean-Baptiste Duboule also would go on to revolutionize the fusee watch design. By the mid-17th century, watches operated with a mainspring made of either a length of catgut or chain. This spring, after the watch had been fully wound, will slowly wrap around a conical spiral as the timekeeper runs during the course of the day. Around 1660, there was a great deal of concern that the chain would not settle properly within the grooves of the fusee spiral. By recontouring the groove, Jean-Baptiste made sure that the fusee chain wouldn't come loose through the normal wear and tear of the watch.

It is due to both father and son's immeasurable talents and contributions to the watchmaking world that we pay tribute. The plethora of beautiful timepieces that make up the Duboule collection are made with a perfect balance of precise craftsmanship and refined presence. So join us as we remember the brilliant watches of the past with these incredible timepieces of today.